We assume that more choice means better options and greater satisfaction. But beware of excessive choice: choice overload can make you question the decisions you make before you even make them, it can set you up for unrealistically high expectations, and it can make you blame yourself for any and all failures. In the long run, this can lead to decision-making paralysis, anxiety, and perpetual stress. And, in a culture that tells us that there is no excuse for falling short of perfection when your options are limitless, too much choice can lead to clinical depression.

“Focus on what makes you happy, and do what gives meaning to your life”

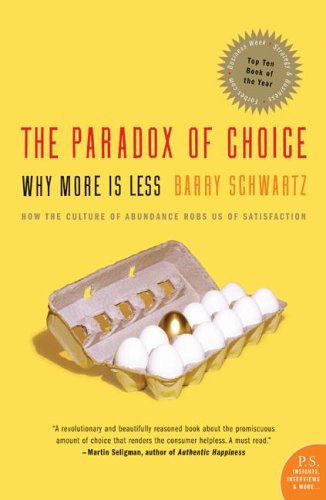

In The Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz explains at what point choice — the hallmark of individual freedom and self-determination that we so cherish — becomes detrimental to our psychological and emotional well-being. In accessible, engaging, and anecdotal prose, Schwartz shows how the dramatic explosion in choice — from the mundane to the profound challenges of balancing career, family, and individual needs — has paradoxically become a problem instead of a solution. Schwartz also shows how our obsession with choice encourages us to seek that which makes us feel worse.

By synthesizing current research in the social sciences, Schwartz makes the counter-intuitive case that eliminating choices can greatly reduce the stress, anxiety, and busyness of our lives. He offers eleven practical steps on how to limit choices to a manageable number, have the discipline to focus on the important ones and ignore the rest, and ultimately derive greater satisfaction from the choices you have to make. [From: Barnesandnoble.com]

“When asked about what they regret most in the last six months, people tend to identify actions that didn’t meet expectations. But when asked about what they regret most when they look back on their lives as a whole, people tend to identify failures to act.”

Schwartz assembles his argument from a variety of fields of modern psychology that study how happiness is affected by success or failure of goal achievement.

When we choose

Schwartz compares the various choices that Americans face in their daily lives by comparing the selection of choices at a supermarket to the variety of classes at an Ivy League college.

There are now several books and magazines devoted to what is called the “voluntary simplicity” movement. Its core idea is that we have too many choices, too many decisions, too little time to do what is really important. […] Taking care of our own “wants” and focusing on what we “want” to do does not strike me as a solution to the problem of too much choice.

Schwartz maintains that it is precisely so that we can focus on our own wants that all of these choices emerged in the first place.

How we choose

Schwartz describes that a consumer’s strategy for most good decisions will involve these steps:

- Figure out your goal or goals. The process of goal-setting and decision making begins with the question: “What do I want?” When faced with the choice to pick a restaurant, a CD, or a movie, one makes their choice based upon how one would expect the experience to make them feel, expected utility. Once they have experienced that particular restaurant, CD or movie, their choice will be based upon a remembered utility. To say that you know what you want, therefore, means that these utilities align. Nobel Prizewinning psychologist Daniel Kahneman and his colleagues have shown that what we remember about the pleasurable quality of our past experiences is almost entirely determined by two things: how the experiences felt when they were at their peak (best or worst), and how they felt when they ended.

- Evaluate the importance of each goal. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky have researched how people make decisions and found a variety of rules of thumb that often lead us astray. Most people give substantial weight to anecdotal evidence, perhaps so much so that it cancels out expert evidence. The researchers called it the availability heuristic describing how we assume that the more available some piece of information is to memory, the more frequently we must have encountered it in the past. Salience will influence the weight we give any particular piece of information.

- Array the options. Kahneman and Tversky found that personal “psychological accounts” will produce the effect of framing the choice and determining what options are considered as subjects to factor. For example, an evening at a concert could be just one entry in a much larger account, of say a “meeting a potential mate” account. Or it could be part of a more general account such as “ways to spend a Friday night”. Just how much an evening at a concert is worth will depend on which account it is a part of.

- Evaluate how likely each of the options is to meet your goals. People often talk about how “creative accountants can make a corporate balance sheet look as good or bad as they want it to look.” In many ways Schwartz views most people as creative accountants when it comes to keeping their own psychological balance sheet.

- Pick the winning option. Schwartz argues that options are already attached to choices being considered. When the options are not already attached, they are not part of the endowment and choosing them is perceived as a gain. Economist Richard Thaler provides a helpful term sunk costs.

- Modify goals. Schwartz points out that later, one uses the consequences of their choice to modify their goals, the importance assigned to them, and the way future possibilities are evaluated.

Schwartz relates the ideas of psychologist Herbert A. Simon from the 1950s to the psychological stress that most consumers face today. He notes some important distinctions between, what Simon termed, maximizers and satisficers. A maximizer is like a perfectionist, someone who needs to be assured that their every purchase or decision was the best that could be made. The way a maximizer knows for certain is to consider all the alternatives they can imagine. This creates a psychologically daunting task, which can become even more daunting as the number of options increases. The alternative to maximizing is to be a satisficer. A satisficer has criteria and standards, but a satisficer is not worried about the possibility that there might be something better. Ultimately, Schwartz agrees with Simon’s conclusion, that satisficing is, in fact, the maximizing strategy.

“Learning to choose is hard. Learning to choose well is harder. And learning to choose well in a world of unlimited possibilities is harder still, perhaps too hard.”

Why we suffer

Schwartz integrates various psychological models for happiness showing how the problem of choice can be addressed by different strategies. What is important to note is that each of these strategies comes with its own bundle of psychological complication.

- Choice and Happiness. Schwartz discusses the significance of common research methods that utilize a Happiness Scale. He sides with the opinion of psychologists David Myers and Robert Lane, who independently conclude that the current abundance of choice often leads to depression and feelings of loneliness. Schwartz draws particular attention to Lane’s assertion that Americans are paying for increased affluence and freedom with a substantial decrease in the quality and quantity of community. What was once given by family, neighborhood and workplace now must be achieved and actively cultivated on an individual basis. The social fabric is no longer a birthright but has become a series of deliberated and demanding choices. Schwartz also discusses happiness with specific products. For example, he cites a study by Sheena Iyengar of Columbia University and Mark Lepper of Stanford University who found that when participants were faced with a smaller rather than larger array of chocolates, they were actually more satisfied with their tasting.

- Freedom or Commitment. Schwartz connects this issue to economist Albert Hirschman’s research into how populations respond to unhappiness: they can exit the situation, or they can protest and voice their concerns. While free-market governments give citizens the right to express their displeasure by exit, as in switching brands, Schwartz maintains that social relations are different. Instead, we usually give voice to displeasure, hoping to project influence on the situation.

- Second-Order Decisions. Law professor Cass Sunstein uses the term “second-order decisions” for decisions that follow a rule. Having the discipline to live “by the rules” eliminates countless troublesome choices in one’s daily life. Schwartz shows that these second-order decisions can be divided into general categories of effectiveness for different situations: presumptions, standards, and cultural codes. Each of these methods are useful ways people use to parse the vast array of choices they confront.

- Missed Opportunities. Schwartz finds that when people are faced with having to choose one option out of many desirable choices, they will begin to consider hypothetical trade-offs. Their options are evaluated in terms of missed opportunities instead of the opportunity’s potential. Schwartz maintains that one of the downsides of making trade-offs is it alters how we feel about the decisions we face; afterwards, it affects the level of satisfaction we experience from our decision. While psychologists have known for years about the harmful effects of negative emotion on decision making, Schwartz points to recent evidence showing how positive emotion has the opposite effect: in general, subjects are inclined to consider more possibilities when they are feeling happy. [From: Wikipedia.com]

“The alternative to maximizing is to be a satisficer. To satisfice is to settle for something that is good enough and not worry about the possibility that there might be something better.”

What others say

“Whether choosing a health-care plan, choosing a college class or even buying a pair of jeans, Schwartz shows that a bewildering array of choices floods our exhausted brains, ultimately restricting instead of freeing us.” — Publisher’s Weekly

Why you should listen

In his 2004 book The Paradox of Choice , Barry Schwartz tackles one of the great mysteries of modern life: Why is it that societies of great abundance — where individuals are offered more freedom and choice (personal, professional, material) than ever before — are now witnessing a near-epidemic of depression? Conventional wisdom tells us that greater choice is for the greater good, but Schwartz argues the opposite: He makes a compelling case that the abundance of choice in today’s western world is actually making us miserable.

Infinite choice is paralyzing, Schwartz argues, and exhausting to the human psyche. It leads us to set unreasonably high expectations, question our choices before we even make them and blame our failures entirely on ourselves. His relatable examples, from consumer products (jeans, TVs, salad dressings) to lifestyle choices (where to live, what job to take, who and when to marry), underscore this central point: Too much choice undermines happiness.

Schwartz’s previous research has addressed morality, decision-making and the varied inter-relationships between science and society. Before Paradox he published The Costs of Living, which traces the impact of free-market thinking on the explosion of consumerism — and the effect of the new capitalism on social and cultural institutions that once operated above the market, such as medicine, sports, and the law.

Both books level serious criticism of modern western society, illuminating the under-reported psychological plagues of our time. But they also offer concrete ideas on addressing the problems, from a personal and societal level. [From: TED.com]

Now watch his video :

TITLE: Barry Schwartz: The paradox of choice

TEDGlobal 2005 · 19:37 minutes · Filmed Jul 2005

See more at TED.com

About the Author:

Barry Schwartz is a professor of psychology at Swarthmore College, in Pennsylvania.

Among his many publications are four books written for popular audiences. The Battle for Human Nature (1986) examines and criticizes the assumptions about human nature shared by evolutionary biology, economics, and behavioral psychology. The Costs of Living (1994) argues that free-market economic and social organization erode some of the best things in life. The Paradox of Choice (2004) shows that whereas choice is liberating, too much choice is paralyzing. And Practical Wisdom (2010, with Kenneth Sharpe) argues that to get the educational, medical, legal and financial systems we want and need, we must nurture character—the will to do the right thing—in practitioners. The Paradox of Choice was named one of the top business books of the year by both Business Week and Forbes Magazine, and has been translated into twenty-five languages.

Schwartz has published articles in sources as diverse as The New York Times, The New York Times Magazine, the Chronicle of Higher Education, Parade Magazine, USA Today, Slate, Scientific American, The New Republic, Newsday, the AARP Bulletin, the Harvard Business Review, and the Guardian. He has appeared on dozens of radio shows, including NPR’s Morning Edition, Talk of the Nation, and All Things Considered, and has been interviewed on Anderson Cooper 360 (CNN), the Lehrer News Hour (PBS), and CBS Sunday Morning. And he has spoken twice—once about choice (2004) and once about wisdom (2009), at the well known TED conference. [From casbs.org]

If you like this story, CLICK HERE to join the tribe of success-minded people just like you. You will love our weekly quick summaries of top stories, talks, books, movies, music and more with handy downloadable guides, cheat sheets, cliffs notes and quote books.

And, you can opt-out at any time – no strings, promise… CLICK HERE