“The brain is a far more open system than we ever imagined, and nature has gone very far to help us perceive and take in the world around us. It has given us a brain that survives in a changing world by changing itself.”

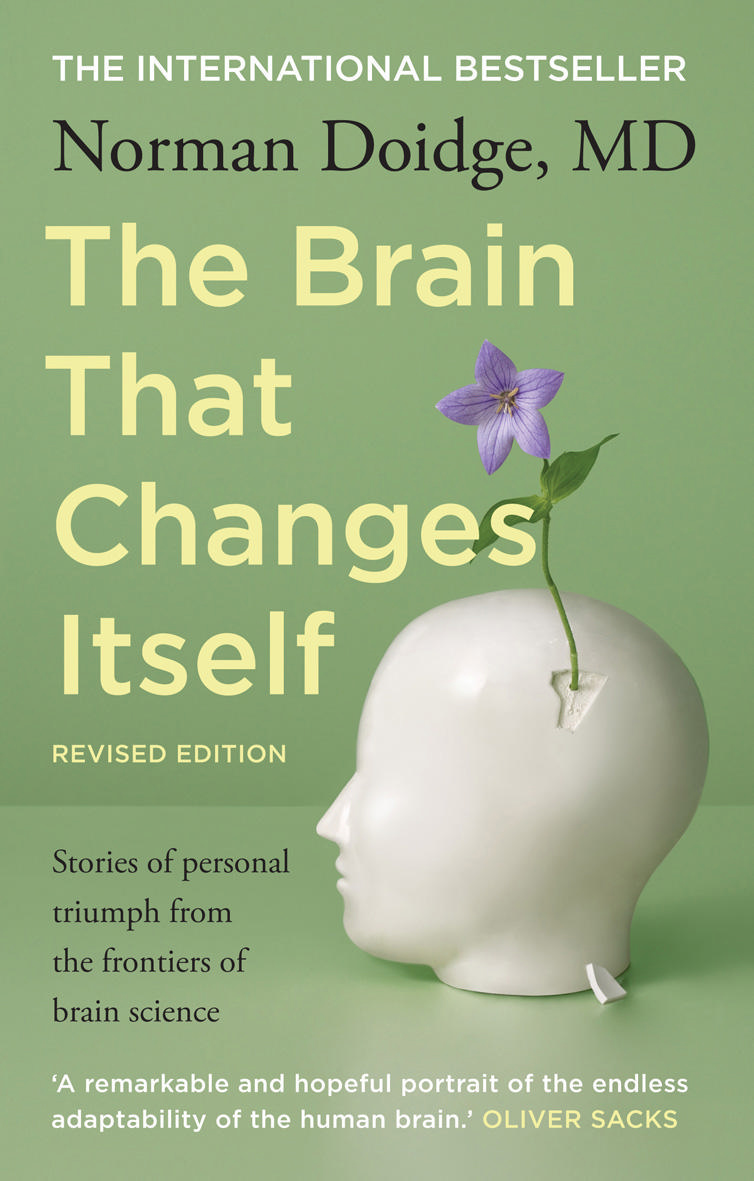

What is neuroplasticity? Is it possible to change your brain? Norman Doidge’s inspiring guide to the new brain science explains all of this and more.

An astonishing new science called neuroplasticity is overthrowing the centuries-old notion that the human brain is immutable, and proving that it is, in fact, possible to change your brain. Psychoanalyst, Norman Doidge, M.D., traveled the country to meet both the brilliant scientists championing neuroplasticity, its healing powers, and the people whose lives they’ve transformed—people whose mental limitations, brain damage or brain trauma were seen as unalterable. We see a woman born with half a brain that rewired itself to work as a whole, blind people who learn to see, learning disorders cured, IQs raised, aging brains rejuvenated, stroke patients learning to speak, children with cerebral palsy learning to move with more grace, depression and anxiety disorders successfully treated, and lifelong character traits changed. Using these marvelous stories to probe mysteries of the body, emotion, love, sex, culture, and education, Dr. Doidge has written an immensely moving, inspiring book that will permanently alter the way we look at our brains, human nature, and human potential. [From: Barnesandnoble.com]

“Psychoanalysis is often about turning our ghosts into ancestors, even for patients who have not lost loved ones to death. We are often haunted by important relationships from the past that influence us unconsciously in the present. As we work them through, they go from haunting us to becoming simply part of our history.”

THE BRAIN CAN CHANGE ITSELF. It is a plastic, living organ that can actually change its own structure and function, even into old age. Arguably the most important breakthrough in neuroscience since scientists first sketched out the brain’s basic anatomy, this revolutionary discovery, called neuroplasticity, promises to overthrow the centuries-old notion that the brain is fixed and unchanging. The brain is not, as was thought, like a machine, or “hardwired” like a computer. Neuroplasticity not only gives hope to those with mental limitations, or what was thought to be incurable brain damage, but expands our understanding of the healthy brain and the resilience of human nature.

Norman Doidge, MD, a psychiatrist and researcher, set out to investigate neuroplasticity and met both the brilliant scientists championing it and the people whose lives they’ve transformed.

WE LEARN THAT OUR THOUGHTS CAN SWITCH OUR GENES ON AND OFF, ALTERING OUR BRAIN ANATOMY

The result is this book, a riveting collection of case histories detailing the astonishing progress of people whose conditions had long been dismissed as hopeless. We see a woman born with half a brain that rewired itself to work as a whole, a woman labeled retarded who cured her deficits with brain exercises and now cures those of others, blind people learning to see, learning disorders cured, IQs raised, aging brains rejuvenated, painful phantom limbs erased, stroke patients recovering their faculties, children with cerebral palsy learning to move more gracefully, entrenched depression and anxiety disappearing, and lifelong character traits altered.

Doidge takes us into terrain that might seem fantastic. We learn that our thoughts can switch our genes on and off, altering our brain anatomy. Scientists have developed machines that can follow these physical changes in order to read people’s thoughts, allowing the paralyzed to control computers and electronics just by thinking. We learn how people of average intelligence can, with brain exercises, improve their cognition and perception in order to become savant calculators, develop muscle strength, or learn to play a musical instrument, simply by imagining doing so.

Using personal stories from the heart of this neuroplasticity revolution, Dr. Doidge explores the profound implications of the changing brain for understanding the mysteries of love, sexual attraction, taste, culture and education in an immensely moving, inspiring book that will permanently alter the way we look at human possibility and human nature. [From: Normandoidge.com]

“All of us have worries. We worry because we are intelligent beings. Intelligence predicts, that is its essence; the same intelligence that allows us to plan, hope, imagine, and hypothesize also allows us to worry and anticipate negative outcomes.”

The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science is a book on neuroplasticity by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Norman Doidge, M.D. It features numerous case studies of patients suffering from neurological disorders and details how in each case the brain adapts to compensate for the disabilities of the individual patients, often in unusual and unexpected ways. Interviews with the patients, clinicians, and research scientists involved in these studies make up a large portion of the contents. Doidge uses examples of previous work carried out by neuroscientists such as Paul Broca, Sigmund Freud, Aleksandr Luria, Donald O. Hebb, Paul Bach-y-Rita, and Eric Kandel to show that the brain is adaptive, and thus plastic. Through the case studies, Doidge demonstrates both the beneficial and detrimental effects that neuroplasticity can have on a patient, saying, “…neuroplasticity contributes to both the constrained and unconstrained aspects of our nature.” However, neuroplasticity “…renders our brains not only more resourceful, but also more vulnerable to outside influences.”

An important example of neuroplasticity is how humans gain skills. Doidge presents an experiment performed by Alvaro Pascual-Leone in which he mapped the brains of blind people learning to read Braille. Braille reading is a motor activity, which involves scanning with a reading finger, and a sensory activity, which involves feeling the raised bumps. The brain maintains a representation of these sensory and motor aspects, which are located in different cortices. The blind subjects practiced two hours a day, Monday through Friday, with an hour of homework. The mapping of their brains took place on Monday, after the weekend, and Friday, immediately after their week cram. What the scans ultimately showed is that the maps dramatically increased in size on Friday scans but returned to a “baseline” size on the following Monday. It took 6 months for the baseline Monday map to gradually increase and by 10 months they plateaued. After the blind subjects took a two month break, they were remapped, and their maps were unchanged from their last Monday mapping. What this shows is that long lasting changes as the result of skill learning took 10 months of repeated practice. The reason why short-term improvements were made based on the Friday mappings, but eventually disappeared, is the result of the type of neuronal connections that were taking place. The Friday mappings were the result of the strengthening of existing neuronal connections. Monday mappings, though showing little progress initially and plateauing at ten months, were the result of the creation of new neural connections. [From: Wikipedia.com]

“Analysis helps patients put their unconscious procedural memories and actions into words and into context, so they can better understand them. In the process they plastically retranscribe these procedural memories, so that they become conscious explicit memories, sometimes for the first time, and patients no longer need to “relive” or “reenact” them, especially if they were traumatic.”

In bookstores, the science aisle generally lies well away from the self-help section, with hard reality on one set of shelves and wishful thinking on the other. But Norman Doidge’s fascinating synopsis of the current revolution in neuroscience straddles this gap: the age-old distinction between the brain and the mind is crumbling fast as the power of positive thinking finally gains scientific credibility.

The credo of this revolution is neuroplasticity — the discovery that the human brain is as malleable as a lump of wet clay not only in infancy, as scientists have long known, but well into hoary old age.

In classical neuroscience, the adult brain was considered an immutable machine, as wonderfully precise as a clock in a locked case. Every part had a specific purpose, none could be replaced or repaired, and the machine was destined to tick in unchanging rhythm until its gears corroded with age.

Now sophisticated experimental techniques suggest the brain is more like a Disney-esque animated sea creature. Constantly oozing in various directions, it is apparently able to respond to injury with striking functional reorganization, and can at times actually think itself into a new anatomic configuration, in a kind of word-made-flesh outcome far more characteristic of Lourdes than the National Institutes of Health.

So it is forgivable that Dr. Doidge, a Canadian psychiatrist and award-winning science writer, recounts the accomplishments of the “neuroplasticians,” as he calls the neuroscientists involved in these new studies, with breathless reverence. Their work is indeed mind-bending, miracle-making, reality-busting stuff, with implications, as Dr. Doidge notes, not only for individual patients with neurologic disease but for all human beings, not to mention human culture, human learning and human history.

And all this from the fact that the electronic circuits in a small lump of grayish tissue are perfectly accessible, it turns out, to any passing handyman with the right tools.

For patients with brain injury, the revolution brings only good news, as Dr. Doidge describes in numerous examples. A woman with damage to the inner ear’s vestibular system, where the sense of balance resides, feels as if she is in constant free fall, tumbling through space like an ocean bather pulled under by the surf. Sitting in a neuroscience lab, she puts a set of electrodes on the surface of her tongue, a wired-up hard hat on her head, and the feel of falling stops. The apparatus connects to a computer to create an external vestibular system, replacing her damaged one by sending the proper signals to her brain via her tongue.

But that’s not all. After a year of sessions with the device, she no longer needs it: her brain has rewired itself to bypass the damaged vestibular system with a new circuit.

A surgeon in his 50s suffers an incapacitating stroke. He is one of the first patients to enroll in a rehabilitation clinic guided by principles of neuroplasticity: his good arm and hand are immobilized, and he is set cleaning tables. At first the task is impossible, then slowly the bad arm remembers its skills. He learns to write again, he plays tennis again: the functions of the brain areas killed in the stroke have transferred themselves to healthy regions.

An amputee has a bizarre itch in his missing hand: unscratchable, it torments him. A neuroscientist finds that the brain cells that once received input from the hand are now devoted to the man’s face; a good scratch on the cheek relieves the itch. Another amputee has 10 years of excruciating “phantom” pain in his missing elbow. When he puts his good arm into a box lined with mirrors he seems to recognize his missing arm, and he can finally stretch the cramped elbow out. Within a month his brain reorganizes its damaged circuits, and the illusion of the arm and its pain vanish.

Research into the malleability of the normal brain has been no less amazing. Subjects who learn to play a sequence of notes on the piano develop characteristic changes in the brain’s electric activity; when other subjects sit in front of a piano and just think about playing the same notes, the same changes occur. It is the virtual made real, a solid quantification of the power of thought.

From this still relatively primitive experimental data, theories can be constructed for the entirety of human experience: creativity and love, addiction and obsession, anger and grief — all, presumably, are the products of distinct electrical associations that may be manipulated by the brain itself, and by the brains of others, for better or worse.

For neuroplasticity may prove a curse as well. The brain can think itself into ruts, with electrical habits as difficult to eradicate as if it were, in fact, the immutable machine of yore. Sometimes “roadblocks” can be created to help steer its activity back in the desired direction (like bandaging the stroke patient’s good arm). Sometimes rewiring the circuits requires hard cerebral work instead; Dr. Doidge cites the successful Freudian analysis of one of his patients.

And, of course, the implications for external re-engineering of the human brain are ominous, for if the brain is malleable it is also endlessly vulnerable, not only to its own mistakes but also to the ambitions and excesses of others, whether they are misguided parents, well-meaning cultural trendsetters or despotic national leaders.

The new science of the brain may still be in its infancy, but already, as Dr. Doidge makes quite clear, the scientific minds are leaping ahead. [From: Nytimes.com]

“For children to know and regulate their emotions, and be socially connected, they need to experience this kind of interaction many hundreds of times in the critical period and then to have it reinforced later in life.”

For years the doctrine of neuroscientists has been that the brain is a machine: break a part and you lose that function permanently. But more and more evidence is turning up to show that the brain can rewire itself, even in the face of catastrophic trauma: essentially, the functions of the brain can be strengthened just like a weak muscle. Scientists have taught a woman with damaged inner ears, who for five years had had “a sense of perpetual falling,” to regain her sense of balance with a sensor on her tongue, and a stroke victim to recover the ability to walk although 97% of the nerves from the cerebral cortex to the spine were destroyed. With detailed case studies reminiscent of Oliver Sachs, combined with extensive interviews with lead researchers, Doidge, a research psychiatrist and psychoanalyst at Columbia and the University of Toronto, slowly turns everything we thought we knew about the brain upside down. He is, perhaps, overenthusiastic about the possibilities, believing that this new science can fix every neurological problem, from learning disabilities to blindness. But Doidge writes interestingly and engagingly about some of the least understood marvels of the brain. [From: Publishersweekly.com]

“No other instinct can so satisfy without accomplishing its biological purpose, and no other instinct is so disconnected from its purpose.”

A collection of anecdotes about doctors and patients demonstrating that the human brain is capable of undergoing remarkable changes. Research psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Doidge (Columbia Univ. Psychoanalytic Center) calls this growing awareness of the brain’s adaptability “the neuroplastic revolution,” and he profiles scientists whose work in neuroplasticity has changed people’s lives. He begins with Paul Bach-y-Rita, a pioneer in brain plasticity who has helped stroke victims improve their balance and walking. Doidge also interviews Michael Merzenich, a researcher and inventor who claims that brain exercises may be as useful as drugs in treating schizophrenia and has also developed training programs for the learning-disabled and the aging. The author talks with V.S. Ramachandran, a neurologist successful in treating phantom-limb pain, and he visits the Salk Laboratories in La Jolla, Calif., to report on the implications of current research on human neuronal stem cells. Some stories focus on nonscientists, such as the brain-damaged woman who developed her own brain exercises and then founded a Toronto school for children with learning disabilities, and a woman who functions well and has extraordinary calculating skills despite her brain having virtually no left hemisphere. The author draws on his own psychoanalytic practice to illustrate how the brain’s plasticity can also create problems, e.g., when early childhood trauma causes massive change in a patient’s hippocampus. One appendix explores the issue of how culture shapes the brain and is shaped by it; another takes a brief look at changing ideas about human nature and its perfectibility. Somewhat scattershot, but Doidge’s personalstories, enthusiasm for his subject and admiration for its researchers keep the reader engaged. [From: Kirkusreviews.com]

“As we age and plasticity declines, it becomes increasingly difficult for us to change in response to the world, even if we want to. We find familiar types of stimulation pleasurable; we seek out like-minded individuals to associate with, and research shows we tend to ignore or forget, or attempt to discredit, information that does not match our beliefs, or perception of the world, because it is very distressing and difficult to think and perceive in unfamiliar ways.”

Now Watch This Video:

Dr. Norman Doidge ,”The Brain That Changes Itself” full show

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3TQopnNXBU

~~~~~~~~ or Read the TRANSCRIPT of the Video ~~~~~~~~

“The Brain That Changes Itself”

Allan Gregg In Conversation with Dr. Norman Doidge

Allan Gregg: For a long time, it was believed that the human brain was fixed or hardwired. In most forms brain damage were there for permanent and irreversible. However, scientists have since come to realize that far from being fixed the brain has remarkable powers to regenerate itself even in old age. Norman Doidge is a psychiatrist and medical researcher. In his new book, he explores the impact of this revolutionary discovery on all of us. It’s called “The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science”. For years we’ve been told that the human brain is like a machine, a computer, that there are different parts that they are responsible for different functions and if those parts break or wear down or damaged we lose that function. Now in your new book, you’ve throw this all on its head and you say that in fact the brain is plastic.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Right.

Allan Gregg: Explain what that means.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Well plastic means plastic in a sense of plasticine, modifiable, adaptable. The plastic brain is a brain that can change its structure and its function.

Allan Gregg: Both?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Both.

Allan Gregg: Without drugs?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Without drugs. Just depending on what you do with your brain, the task at hand that you are working on. What you’re perceiving can cause you to change the structure of your brain on many levels. And this is the most fantastic part, what you think and imagine actually can change the structure of your brain down to the very connections between the brain cells, down into the genes even. For instance, you know one of the most, you know, staggeringly interesting discoveries of the late 20thcentury was the discovery that learning changes the number of connections between the neurons, the nerve cells in the nervous system. You can go for instance, from having perhaps 1300 connections between nerve cell A and nerve cell B to 2700 with several hours of training.

Allan Gregg: By virtue of more brain activity incurred?

Dr. Norman Doidge: By virtue of learning in brain activity. So what happens is thoughts or activities that you do with your brain actually turn certain genes on and others off inside the nerve cells which then make proteins which then change the structure.

Allan Gregg: Now, why is this discovery considered so revolutionary? More particularly, what are the implications of this discovery for people with brain dysfunction? Stroke for example.

Dr. Norman Doidge: When you had a stroke, the general assumption was your brain got swollen, the chemicals were kind of deranged and after a few weeks whatever you are left with was what you have to live with the rest of your life.

Allan Gregg: You basically lost that brain function that was damaged?

Dr. Norman Doidge: The cells died. They couldn’t be replaced. The healthy ones around it couldn’t reorganize and so we were kind of waiting for the swelling to go away and rehab is just sort of focused on getting you over that period. Now we know that rehab can actually reorganize the brain if it’s done properly and bring many new functions back. But if I need to say it, it also meant that as you started to get older and your brain started to decline, it was like a machine that was wearing out and the attempt to exercise your brain in the second half of life was really kind of unwarranted or waste of time and so we just accepted a view of human development in which the second half of life is a period of necessary mental decline. And then of course the whole view of human nature that we have, you know, since the rise of modern science, most educated people see human nature in some ways emerging from the human brain. And if the human brain was fixed, immutable and a rigid structure, it made a lot of sense to think of human nature is fundamentally fixed and so we have to reexamine all that and I begin to do that in this book.

Allan Gregg: Well, you do it by way of story and that there’s some remarkable almost logic defying remarkable given what our traditional notion with the brain is. Probably the most remarkable here is the story of a woman who was born with half a brain.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Yeah.

Allan Gregg: Tell me about Michelle.

Dr. Norman Doidge: I went to visit Michelle because I thought that, I knew that she did have half, was born with one hemisphere alone, just half a brain, and I thought that whatever changes that she was able to undergo would really test this notion of plasticity certainly at least in an early life. And, basically, when she was in the womb some catastrophic event occurred. So, her left hemisphere never developed. And based on the usual view of that the brain basically has certain areas which in the left hemisphere which are responsible for speech and other functions.

Allan Gregg: Right.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Someone with that level of damage you would imagine would be unable to speak, unable to think, they might be alive but on a respirator. And it turns out that that’s not the case with Michelle. In fact, if you met Michelle, you would detect some subtle things like one of her arms is a little twisted, etcetera, and her speech when she’s upset it’s a little repetitive. But you would never dream and nor did the people who examined her for a number of years dream that she had half a brain.

Allan Gregg: Explain this now. If we had though that, okay, this part of the brain is responsible for speech and I don’t have this part of the brain, how is Michelle speaking?

Dr. Norman Doidge: We know that there’s a lot of plasticity early in life. But we also know and I make this very clear in the book, there’s plasticity from cradle to grave. But you know, there are waves of increased plasticity and it turns out that what the brain does is it learns how to do what it’s got to do at the time. So, parts of the brain that might have been devoted to other things will learn how to move. If it has to see to survive, they’ll be devoted to vision. And so, all these things can actually reorganized and move around, these higher mental functions.

Allan Gregg: To give our viewers even more kind of appreciation of the extent to which that’s possible. We tell the story that’s in the book that you dubbed “The woman who was perpetually falling”.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Sheryl Siltz was a woman. She had a hysterectomy and she was given a medication because she developed an infection called gentamicin and it poisoned the vestibular apparatus which is the balance apparatus in her brain.

Allan Gregg: Right.

Dr. Norman Doidge: And if you lose your sense of balance, you will feel like you are perpetually falling. When I was with Sheryl at one point, I asked her what it’s like when you’ve finally fallen to the floor. What is the feel at that point? And then she says sometimes I just feel the floor opens up and I fall into a perpetual abyss. So that was her life and she ended up on a disability. And one of the great people who were at the cutting edge, I call these people neuroplasticians to go in a phrase. Paul Bach-y-Rita invented a mechanism and I was there when she was using the mechanism for one of the first times that basically was attached to an accelerometer and accelerometers are just like a gyroscope. The accelerometer would be in a hat on her head.

Allan Gregg: Like a construction hat?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Like a construction hat and it would give signals that went into her tongue of all places telling her where she was in space. I tried it on so you lean forward and you feel like champagne bubbles. They’re really little electric shocks tell you to forward you lean back it goes back. And she would put this hat on and immediately, she would, normally she’d be holding herself up in the table unless she’ll fall and immediately her whole body relaxed. This seems like a miracle why because the sensory apparatus, the sense of touch on the tongue goes to a different part of the brain in the balance apparatus. So somehow or other these signals coming in, were making new pathways for strengthening very dormant pathways between her sense of touch and her sense of balance. So that was the first miracle. I saw that happening. She had tried it on and then there was a second miracle which is as she started to use the machine more. She found she had a residual period where she would take the hat off and at first the residual period lasted 30 seconds.

Allan Gregg: Residual period being that she still had balance and then the same effect even though the hat was off?

Dr. Norman Doidge: It lasted for, you know, a few seconds and then it lasted longer and longer and as she started to use the hat and take it home and use it, she would be going for days and that was a true miracle because what was happening. I mean it’s only a miracle if you think that the brain is fixed.

Allan Gregg: Right. Right.

Dr. Norman Doidge: It’s actually not a miracle because she now no longer considers herself a wobbler.

Allan Gregg: Because the brain reordered itself and put the balance in a different part of the brain, wasn’t it?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Yeah! And it developed new path.

Allan Gregg: Now, is this sensory substitution? I mean is this again another falsinating notion you introduced in the book?

Dr. Norman Doidge: This is what Paul Bach-y-Rita called sensory substitution. He did this as well for people who’ve been congenitally blind, they’ve never seen anything and he rigged up a camera to a computer and then attached it to the back and there were vibrating pixels that were on the back and then he put it in through the tongue and he found that he could train a human tongue to function like a retina. And they will be able to see twiggy. They would usually say well that’s a picture of twiggy, that’s a picture of a vase, you’ve just moved a vase in front of the telephone. They could read certain things. If you threw a ball at them, they would dock. They could see perspective. I mean so this is remarkable events.

Allan Gregg: They can see through their tongue?

Dr. Norman Doidge: What was happening is that the tongue is like a two dimensional surface just as the retina. And yeah, basically.

Allan Gregg: That the images would be projected on the brain.

Dr. Norman Doidge: The image would be on the tongue and then we’ve recently learned actually this was some work also done in Canada Bach-y-Rita is from the states that the input coming into the tongue was processed in the back of the brain which we tend to call the visual cortex. So it was all being rerouted and Paul Bach-y-Rita’s found different ways to do sensory substitution which is lay the ground work for the notion of a retinal implant but also other, you know, helping other people who have lost, literally lost the ability to sense certain things.

Allan Gregg: We touched on the whole issue of stroke victims and you can tell a great story here about a surgeon in his mid-50s that had a terribly really bad debilitating stroke. Tell me how he came back.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Michael Bernstein was out, he was playing tennis. He spent the morning doing surgery on the eyes so he needs a lot of fine motor skills. It’s microscopic surgery. It’s in a small confined space. Then he was playing tennis, then he developed a stroke and he couldn’t move one side of his body. He went for conventional rehabilitation. They gave him whatever it was to four to six weeks. And then basically they said you’re on your own and he had very very little control of his arm at that point and very little control of his leg and then he tried a new form of treatment. He happened to be from Birmingham Alabama where a man named Edward Taub had developed this new treatment called constraint induced therapy. One of the things that neuroplaticians have shown in hundreds of experiments now is that it’s a use it or lose it brain. If you don’t lose, if you don’t use something its state that cortical real estate is taken over by something else. Now what happens when a very common form of stroke is that you have a stroke in the left hemisphere and you can’t move your right hand.

Allan Gregg: You’re paralyzed on that side.

Dr. Norman Doidge: You can’t move it well, etcetera. And so people try to use their arms, it doesn’t work. So, they stop using them. Now what how did ingeniously was he got people to put their good hands in slings and constrain them. And then if a person could just do this, he would give them small amounts just to get a little more control over that, very incremental and he worked them very very hard. And they would have to do things like, you know, try to wash pots. People would come in they couldn’t dress themselves, they couldn’t eat, they couldn’t put food on the fork. They literally would have been dependent for the rest of their lives. And Michael Bernstein is one of the first to go through this and after two weeks of very intensive training, that’s not a long time.

Allan Gregg: No, it isn’t!

Dr. Norman Doidge: He was able to function, get back to work and function as a surgeon. And there are people who went to Taub’s clinic, who there was one person I spoke to who had a stroke of almost 50 years before. He’d been a little boy playing baseball and he had a stroke. They could help him. All these years after the fact, that’s just so remarkable because that plasticine and the ability to reorganize is in the brain. And it has even help people who’ve had traumatic injuries, traumatic brain injuries. I think that’s the kind of thing that would be very helpful for anyone who’s got those, well not anyone, but many people with traumatic brain injuries. For instance, think of the soldiers coming back from Afghanistan.

Allan Gregg: Is this kind of therapy? Or are these kind of treatments now finding their way into medical practice?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Not quite.

Allan Gregg: Because normally when someone has a stroke or any kind of brain damage, I mean we really do look on a very very fatalistically and if the evidence is what we should they don’t improve.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Yeah. We look on it fatalistically in part because studies that has been done in the past and people with brain damage and strokes show that interventions didn’t work but now that the neuroplasticians have laid out the laws of this new science. There’s a reason to be hopeful for a number of kinds of brain injuries.

Allan Gregg: I bet. The notion of phantom pain again documented that people who lose limbs and say continue to hurt. You again claim that neuroplasticity both explains this and that researchers using the theories of neuroplasticity have been able to cure phantom pain. Tell me about that.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Well phantom pain was one of the great mysteries of medicine. How is it possible to feel the pain in the limb that isn’t there? And what a neurologist named Ramachandran discovered was that in patients who’ve lost their arms and then get pain or in one case unscratchable itches, what happens is if you remove an arm, there’s cortical real estate if you will that have been devoted to moving that arm and feeling for that arm, it’s now dormant.

Allan Gregg: In the brain?

Dr. Norman Doidge: In the brain, yes. So, adjacent cortical real estate takes it over and in the typical human body map, an area that’s very close to the arm is actually the face and we now know that phantom pains often cause because the face maps in the brain say “Hey, there’s more cortical real estate for us” and they start to move in there and reorganize the brain. There was one patient who had an unscratchable itch. So that was a terrible affliction for him. And Ramachandran eventually figured that if he just scratch the man’s cheek, the itch went away. Ramachandran was able by the way to sort of trick the brain into rewiring itself using this same neuroplasticity. One of the reasons that people would have these frozen pains is because once the input is stopped into the brain from the arm it’s as though that’s the picture that remains in the brain. There’s no new, there’s no new input to say now the arm is moving again. Many people who had phantoms felt there arms were frozen and in pain. So he set up a mirror device where you would look at your real arm, let’s say this arm have been cut off, you’d look at your real arm and then you’ll look into a mirror right here.

Allan Gregg: The brain would be tricking you thinking that your arm was cut.

Dr. Norman Doidge: And you think that your left arm is moving which of course didn’t exist just kind of put a stamp near it and that rewired the map so that the frozen phantom could move.

Allan Gregg: Now I understand that neuroplasticity also tells us something about the nature of sexual attraction and love. What’s that?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Yes, this tremendous variation of course about people are turned on sexually. I mean take situations in other cultures seem unnatural sometimes and we learned that people can develop attractions if you think of the whole idea that Chinese men a hundred years ago when the aristocracy were totally turned on by women who had their feet broken and banged around. Okay, we start to realize that sexual tastes can be acquired and we can acquire sexual types. And we’re seeing a lot of this happening now actually with the Internet, the Internet porn in a way. There are lot of stories that started to become public in the 90s about men who would get on the Internet and they’d sort of be searching around and then they pass it on to certain images that would really turn them on that really surprised them and then they would practice them over and over and over again and they would have orgasms. And when a person has an orgasm there’s a brain chemical called dopamine which actually reinforces the circuit and rewards them. So dopamine is a neurotransmitter or a brain chemical that’s very involved in consolidating a new circuit and these men would start to develop new sexual attractions that at times seemed bizarre to them. Sometimes they dipped into childhood things. I mean one story I talked about in the book is a man who developed an attraction to spanking sites, and if you think about it, spanking would seem to have to do with early childhood. The other thing that was happening for these men and this was reported over and over and I saw at clinical practice is they said that from a mysterious person they were losing interest in their own partners even though objectively they found them to be attractive. So here was a case where because of plasticity people were inadvertently rewiring their brains and plasticity is not always a good thing.

Allan Gregg: That it can lead to rigid behaviors.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Yeah, in this case in leads typically are very frequently to a kind of an addiction and if you think about it addictions are about plastic change in the brain. There are certain people who if they have alcohol they have a chemical sequence that’s fired in their brain a chemical called delta FosB is released that changes their brain permanently that’s why sometimes it doesn’t make sense for a person to say even if they haven’t had a drink for years “I’m an alcoholic”. It’s in plasticity terms my brain has been structurally altered by my interactions with alcohol.

Allan Gregg: Now, interesting you say that because we also point out that psychoanalysis can be used to open up the brain pathways and reorder the brain’s function. I think you call this neuroplastic therapy. Explain to me what that is and how it would work.

Dr. Norman Doidge: It turns out based on what I’ve told you before about you know thoughts altering genetic behavior that thoughts in therapy are actually changing brain structure as well. They change different brain structures but the major therapist that we know that are successful and that includes psychoanalytic therapies, cognitive behavioral therapies, something called interpersonal therapy, they’re all for slightly different conditions. All rewire the brain, all changed the balance in the brain’s department. So, they are as everybody’s biological if you will an intervention as the use of drugs and the advantage of psychotherapies if you don’t absolutely need drugs and I want to say it I mean I use drugs sometimes but the advantage of them is they don’t have as many side effects in general and if you think about it drugs as they are today are very blunt instrument. You take a pill and it goes every cell in your brain and in fact in your body and that’s why we get so many side effects and it would be in to a certain extent if you’re using thoughts for the intervention you’re like more like a Michael surgeon going into the thought patterns.

Allan Gregg: Do you know enough about the brain to be that precise in terms of psychiatry and psychoanalysis?

Dr. Norman Doidge: In other words if I make an interpretation about the meaning of behavior do I know where in the brain it’s going? Well, if we’re treating let’s say an anxiety problem right, we now know that with the psychoanalytic psychotherapy and you take a person before the therapy and you take the thing that’s making them anxious and you make them think about it or attend to it, the part of the brain that’s likely to light up and trigger the sort of bolts of anxiety and after they go through the therapy, if the therapy works those parts of the brain aren’t triggered.

Allan Gregg: Now you have an absolutely horrifying statistic here about our generation. The baby boomers born between 40 and 60 that they have over 50% chance of reaching the age of 85 and that 85-year-olds have a 47% chance on having Alzheimer’s. We’ll going to have a population full of dementia. What can baby boomers do to enhance their brain power and ward off that disease?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Okay, so there’s two things that we worry about when we think of mental decline as we get older. One of them is a more benign thing and more common it’s called age-related cognitive decline, the senior moments that begin in our 50s that frighten people and then there are this serious dementias. The good news is that we know for a fact now that age-related cognitive decline is reversible through brain exercises and I met with a man Stanley Caransky who was ninety who started to have some difficulties with senior moments. His handwriting was sloppy, he was no longer alert, he was not socializing much and in six weeks roughly an hour a day he was able to reverse all of that.

Allan Gregg: What was he doing?

Dr. Norman Doidge: He was doing a program called Posit Science that I described in the book.

Allan Gregg: Now this is a company, an actual company. Tell me more about this because you’re claiming 80-year-olds feel like 50-year-old.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Well, they’ve shown it. Posit Science was set up by perhaps the world’s leading neuroplastician and neural plasticity researcher Michael Merzenich. And he’s already a man of great accomplishment. He was one of the inventors of the cochlear implant that allows the deaf to hear. He’s helped kids with learning disabilities with reading disabilities moved from problems to basically normal or above normal levels. And they set up a program that rebuilds the auditory cortex, the part of the brain that processes language from scratch in older people. What happens is that as we age one of the reasons that we cannot remember things is our brain maps for sounds are just kind of getting dulled. They need to be tuned up at the very basic level of distinguishing sounds like “ba” and “da” and “pa”. The reason is we haven’t really used them intensively. Often once we hit middle age we are usually playing mastered skills but to maintain a brain in good shape you’ve got to work as hard as you work when you were learning the French vocabulary in high school. Maybe it didn’t work out but as hard as you should have worked out. And so people go for decades without putting themselves for that intensive kind of training. And the cortex just kind of gets dull and you develop what are called fuzzy engrams. You don’t hear the sound of the person’s name at the party crisply so they rebuild it from the ground up.

Allan Gregg: How would our viewers get this program?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Posit. P-O-S-I-T Science. Just go put that in the Internet and then you’ll come to the website.

Allan Gregg: What do you think the next big breakthrough is in brain research? What’s that next big thing we should be watching for?

Dr. Norman Doidge: It’s the translation of the fundamental laws of brain plasticity into applications for everything in therapeutics, in all kinds of training. You know that means sports, the military, education, anything you want to do and develop. Right now, basically, many of these disciplines have an intuitive grasp of some of the laws of plasticity. But the neuroplasticians can help sharpen and speed up learning. So that’s where I imagine it would come. I know that people would want to get very hifalutin and try to facilitate neuroplastic change with chemicals and some of that might be doable but that’s also very problematic for the reason I said that chemicals are still a very blunt instrument.

Allan Gregg: At a personal level, I mean, this book is full of very not just amazing but inspirational and uplifting stories. Over the course of doing the research did it kind of change your sense of what human potential and perhaps human nature is?

Dr. Norman Doidge: Yes it did! One of the most important insights I think I had while doing the book was what I call the plastic paradox. And that is this, the plasticity, the brain is always plastic but it can give rise to both flexible or rigid behaviors. It can give rise to rigid behaviors because once those networks are established, they tend to outcompete the other one in a war of nerves that’s going on inside our head. The human brain is a habit forming thing. So the way to understand plasticity is to think of it as like the hill, a snow in the hill in a winter and we want to ski down that hill so we get to the top of it because the snow is plastic or pliable, we can take many pass down that hill. But it being a hill it has rocks and trees we’ll be inclined towards certain favorite pass. Now, as we keep using those paths, again precisely because the snow was pliable and plastic without tracks and ruts and what we do in our lives is we tend to think that because we’re stuck in a rut and repeating something that not only is the behavior rigid but the underlying brain is rigid. So, when I’m working with patients, I try not to get fooled by the plastic paradox and they’re often fooled by the plastic paradox and I would submit that all of humanity to a large degree has been fooled by the plastic paradox. I think we’ve underestimated how plastic our brains really are.

Allan Gregg: Dr. Norman Doidge, I want to thank you very much for joining me. It’s been fascinating and a real pleasure.

Dr. Norman Doidge: Thank you!

~~~~END

If you like this story, CLICK HERE to join the tribe of success-minded people just like you. You will love our weekly quick summaries of top stories, talks, books, movies, music and more with handy downloadable guides, cheat sheets, cliffs notes and quote books.

And, you can opt-out at any time – no strings, promise… CLICK HERE