“highly successful people have three things in common: motivation, ability, and opportunity.”

“If we create networks with the sole intention of getting something, we won’t succeed. We can’t pursue the benefits of networks; the benefits ensue from investments in meaningful activities and relationships.”

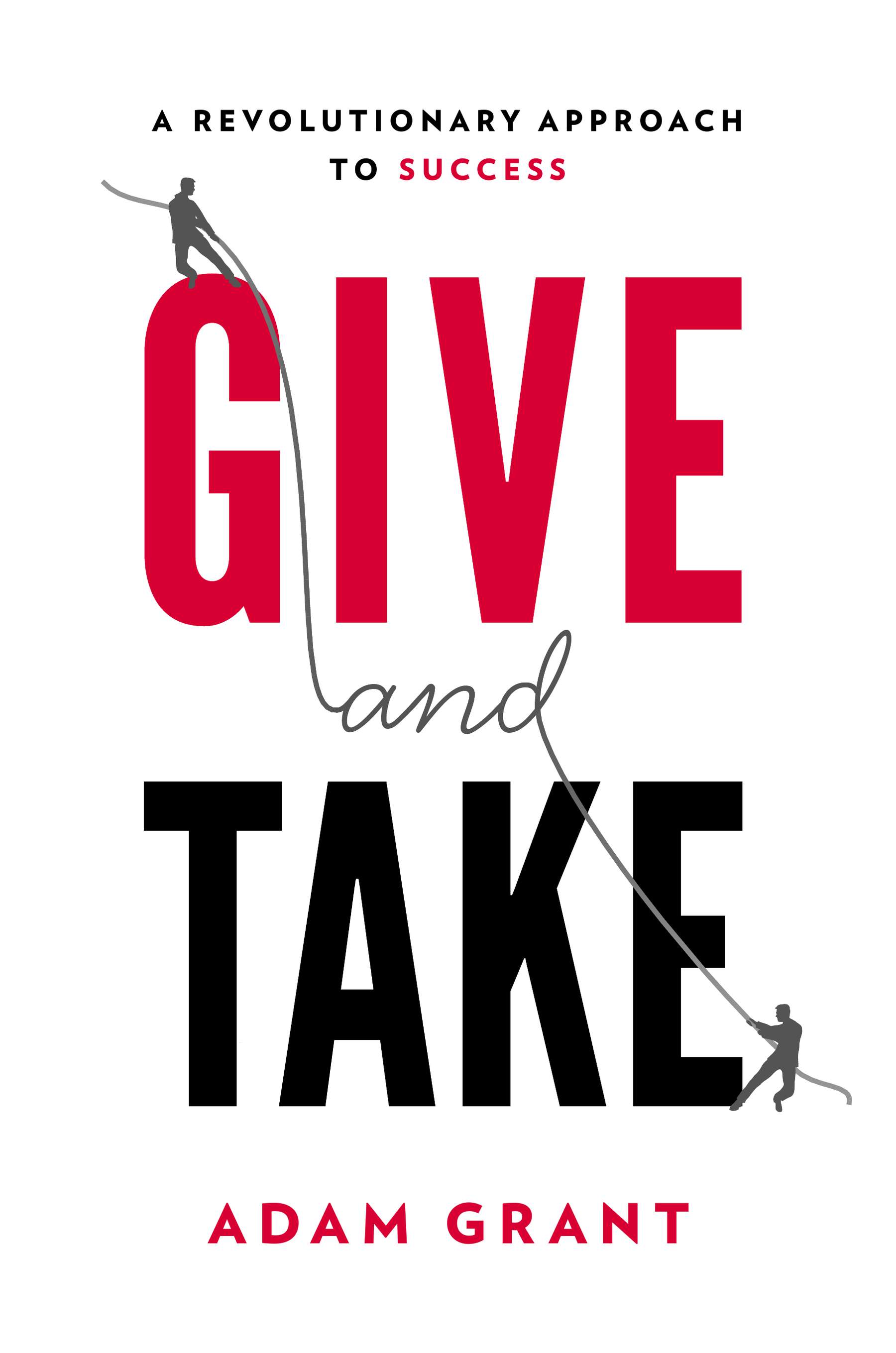

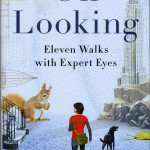

“An important book, destined to be a classic.”

Pay it forward—the idea to give and create value before you expect to be compensated for your work—is a central premise of modern marketing. A parallel old school classic success principle is to do more than you’re paid for—in the vocabulary of commerce, to give more than you get—and in time you’ll be paid for more than you do. Another human relations 101 idea is to invest in the trust bank: Do good now, continue to do good over time, and eventually your virtue will be rewarded.

Samuel Johnson proclaimed: “The true measure of a man is how he treats someone who can do him absolutely no good.” Adam Grant’s Give and Take may be considered an exposition, amplification, and interpretation of Dr. Johnson’s wisdom.

Adam Grant writes: “Takers have a distinctive signature, they like to get more than they give. They tilt reciprocity in their own favor, putting their own interests ahead of others’ needs. Takers believe that the world is a competitive, dog-eat-dog place. By contrast, givers . . . tilt reciprocity in their direction, preferring to give more than they get. Whereas takers tend to be self-focused . . . givers are others focused.”

The author sharply differentiates the two styles, writing, “Givers and takers differ in their attitudes and actions towards other people. If you’re a taker, you help others strategically, when the benefits to you outweigh the personal costs. If you are a giver, you might use a different cost-benefit analysis: you help whenever the benefits to others exceed the personal costs.”

In between are matchers, who seek balance in their interactions through returning the favors done to them and expecting others to reciprocate in kind.

Give and Take combines the author’s own path-breaking studies; summarizations of the collective research in the field, very much in the spirit of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow; and case studies of those who have been extraordinarily successful in ways that may seem counterintuitive, including venture capitalists, Abraham Lincoln, entrepreneurs, lawyers, and sports executives.

Just as Susan Cain makes the case in Quiet that there are far more introverts than is generally recognized, so, too, does Adam Grant proclaim that givers are far more prevalent than commonly understood.

Adam Grant advances the provocative proposition that givers enjoy a powerful comparative advantage over takers. His message is that the succeed-at-any-expense takers’ tactic is a dangerous, ultimately ill-fated success strategy. In particular, Give and Take is a searing indictment of the takers’ tactics of grasping, maneuvering, and manipulating corporate executives who literally take from their colleagues and customers; and who by their pursuit of egregious unethical misconduct literally take from their company’s customers, colleagues, and shareholders. The putative poster boy of this unsustainable style is Ken Lay, former Enron CEO, who exemplified that “takers may rise by kissing up, but they often fall by kicking down.”

Importantly Adam Grant outs the ill-conceived and ultimately destructive policies of such heavy-handed, hard-hearted executives as Jack Welch, who insisted that employees rated in the bottom 10 percent regularly be terminated. Such fear-inducing policies both suppress giving, and also blatantly disregard the proven managerial workplace psychology principle that workers’ performance is strongly influenced by their superiors.

The wrong-headed cultural consequences of those who subscribe to the misinformed Jack Welch managerial philosophy is succinctly summarized by Adam Grant’s observing that there is “evidence that just putting on a business suit and analyzing a Harvard Business School case is enough to significantly reduce the attention that people pay to relationships and to the interests of others.”

He writes, “If I asked you to guess who is the most likely to end up at the bottom of the success ladder what would you say? Takers, givers or matchers?” The provocative answer: “The worst performers and the best performers are givers; takers and matchers are more likely to land in the middle.”

For all the brilliant gifts that Adam Grant provides us in Give and Take, certain of his stories and mini-case studies might be more carefully crafted and more nuanced in their interpretation. While citing Michael Jordan as exemplifying a “self-absorbed and egotistical” taker, he omits the critical story of how Phil Jackson, when assuming the role as coach of the Chicago Bulls, persuaded the legendary basketball great to realign his game, so as to be more giver than taker.

In particular, Coach Jackson instructed his star that if he would focus on improving the performance of and making his team members more successful, he would expand his impact and ultimate success, and thereby become the best individual basketball player and also the leader of the best basketball team. Notably, Michael Jordan reconfigured his game, in the process becoming even more dominant and prominent. As he did less alone, when game circumstances dictated the appropriateness of more selfish play, he was even more effective.

The author—one of Wharton’s top rated professors, an in-demand speaker and advisor, and who is noted for selflessly helping others both documents the giver style and also models his message, through acknowledging nearly 300 named people for their “feedback, wisdom, knowledge and experience . . . wealth of innovative ideas . . . help . . . encouragement.”

At a time when marketing is moving from manipulation to meaning, when consumers seek the authentic over the plastic, when people more and more seek work that embodies their values and purposes, the implications of the message of Give and Take are profound, for “There’s something distinctive that happens when givers succeed: it spreads and cascades . . . creates a ripple effect, enhancing the success of people around them.”

An important book, destined to be a classic. [From: Nyjournalofbooks.com]

“The more I help out, the more successful I become. But I measure success in what it has done for the people around me. That is the real accolade.”

Are you a giver? A taker? A matcher?

In his new book Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success, organization psychologist and Wharton professor Adam M. Grant cites research showing the majority of workers develop a primary reciprocity style: giving, taking or matching.

According to Grant, takers tend to get more than they give, while givers on the job are rare. He writes that outside the workplace, giving is common, but professionally we compartmentalize.

Givers are generous with their ideas, time and skills and share with others who might benefit from them. Grant authored Give and Take to uncover whether givers are actually at a disadvantage because they make others better off while sacrificing their own success.

The fear of exploitation generally prevents many from operating as givers in the workplace. Grant cites Cornell economist Robert Frank, who proposes this fear makes us overly self-preserving, so we tap down our more magnanimous impulses.

Grant argues our impulses for giving are universal and cites the research of psychologist Shalom Schwartz, who studied the values that matter to people in Australia, Chile, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Malaysia, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Sweden and the United States. Schwartz asked respondents in a survey to rate the importance of different lists of values.

Givers favored the list of values that include helpfulness (working for the well-being of others); responsibility (being dependable); social justice (caring for the disadvantaged); compassion (responding to the needs of others). Takers favored the list of values that include wealth (money, material possessions); power (dominance, control over others); pleasure (enjoying life); winning (doing better than others).

Schwartz found that the majority of people endorse giver values above taker values… in every country he surveyed. All of them. Giver values are the most important guiding principles everywhere on the planet.

Parents teach their children that giving and generosity are important guiding principles at home, at school, at play. Yet, we don’t see the importance of giving reciprocity styles in our professional lives. In the workplace, we hide our generosity to prove our competitiveness.

Grant argues that we can be both kind and competitive in the workplace and shows how successful givers are more champs than chumps and every bit as ambitious as takers.

In the chapter “The Ripple Effect,” Grant shares the story of George Meyer, comedy writer/producer at Saturday Night Live, Late Night with David Letterman and The Simpsons.

According to Grant, there is a reality of collaboration behind most brilliant work and Meyer is no lone genius generating great comedy in isolation. Because he is highly talented and might take sole credit for his work, Meyer risks being resented or undermined by other writers.

Instead, Meyer has become known for generously giving away credit for gags. In what Grant calls expedition behavior, Meyer also takes on tasks that are in the best interest of his team. He has earned idiosyncrasy credits, positive impressions accrued in the minds of other writers.

Meyer even has a giver’s code of honor:

(1) Show up.

(2) Work hard.

(3) Be kind.

(4) Take the high road.

Nothing objectionable about encouraging workers to become more otherish. Yet, the book winds up proving how matching is actually the more advantageous reciprocity style, particularly in the chapters on powerless communication, maintaining personal motivation for giving and avoiding exploitation by takers.

The title of the book is also a dead giveway. Through give and take, two parties show a willingness to reciprocate in a balanced discussion. Not to give more, not to take more, but to match.

Grant’s reading of data on reciprocity styles disguises his intention. Proposing that givers in the workplace tend to perform at the bottom, he reveals after a closer look at the data that the generous also perform at the top with takers and matchers landing in the middle.

Grant argues that givers can learn “to harness the benefits of giving while minimizing the costs.” Givers can tweak their selfless reciprocity style with generous tit for tat, advocating for others in negotiations and expanding the pie for everyone.

In other words, high-performing givers in the workplace over time have grown comfortable with matching. Nudging other people away from taking and toward giving contributes to the perception that only through generosity can we flourish and draw satisfaction from our work.

Give and Take by Adam Grant is a worthwhile read on the social science of reciprocity styles, the benefits of giving over taking and how to encourage more generosity in the workplace. [From: Bookkvetch.com]

“Being a giver is not good for a 100-yard dash, but it’s valuable in a marathon.”

Contrary to popular belief, good guys don’t always finish last, and, in fact, an altruistic mindset can help people get ahead professionally. Whenever we interact with others in a business situation, we need to decide how to comport ourselves: focus on our own goals, or give without worrying what we’ll get in return. A giving personality has the power to launch a career or deep-six it. Wharton professor Grant uses psychology and behavioral economics to explain how and why givers can succeed or fail. While takers are often very successful (Ken Lay, for example), they frequently lose credibility. Givers, on the other hand, are better salespeople and are more likely to be believed. Grant shares the stories and philosophies of givers and takers, including comedian George Meyer (a writer and executive producer for The Simpsons) and Craig Newmark of Craigslist. Through Grant acknowledges that taking is sometimes necessary, for most people, giving is not only the best way to succeed professionally, but to be happy. Ending with “actions for impact” so readers develop the right mix of mostly give and some take, Grant drives home programmer and networking genius Adam Rifkin’s five-minute rule: “You should be willing to do something that will take you five minutes or less for anybody.” [From: Publishersweekly.com]

“Partners overestimate their own contributions. This is known as the responsibility bias: exaggerating our own contributions relative to others’ inputs. It’s a mistake to which takers are especially vulnerable, and it’s partially driven by the desire to see and present ourselves positively.”

A scholarly discussion on the push and pull of business ethics. Do good guys really finish last? Grant, an organizational psychologist and prominent Wharton professor, hopes to convince readers otherwise with a book chock full of testimonial stories from businessmen and social scientists on the pros and cons of both giver and taker mentalities. Attitudes in the workplace, he writes, tend to be predominantly of the “matcher” variety (“governed by even exchanges of favors”), whereby a reciprocal balance is strived for and looks good on paper but isn’t always achieved. He notes that givers are looked upon as too soft and trusting, while takers are perceived as callous and hyperdominant. The author provides lively, supplemental case histories from industry givers and takers, like Enron scandal kingpin Kenneth Lay, benevolent online entrepreneur Adam Rifkin and Craigslist’s Craig Newmark, as well as lawyers, hip-hop magnates, teachers and historical greats like Abraham Lincoln and Frank Lloyd Wright. Grant seeks to persuade readers that altruistic givers are too-often underestimated in the business arena, and while some play doormats, many become uniformly successful. He explores the productive nuances of business networking, customer-relationship–building, and practiced, effective communication. In cross matching their characteristics, Grant intimates that there are attributes to be gained in business and career management by being a giver or taker, but he recognizes that a smart combination of both will prove the most effective. He offers “Actions for Impact” to best apply his principles, and his approach is consistently prosocial for readers in every aspect of the business world. Slick strategies and a fresh approach for business professionals wishing to tip the scales of reciprocity. [From: Kirkusreviews.com]

“The fear of being judged as weak or naïve prevents many people from operating like givers at work.”

If you like this story, CLICK HERE to join the tribe of success-minded people just like you. You will love our weekly quick summaries of top stories, talks, books, movies, music and more with handy downloadable guides, cheat sheets, cliffs notes and quote books.